Two Diagrams: America's Past and Present

There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement.

– Lord William Kelvin, 1900 A.D.

Other than relativity, quantum physics, and many other discoveries that I won’t Google just to look smart, Lord Kelvin was spot on. If there is any lesson to take away from his quote, other than how to ruin your legacy in one sentence, it is the vital difference between what is possible and what we think is possible.

OUR BRAINS ARE HARDWARE AND OUR KNOWLEDGE IS SOFTWARE

Elon Musk, among many others, routinely compares the human brain to computer software. By updating our software regularly, what we think is possible inches closer and closer to what is possible.

Like many of the stars in the night sky that seem so real to us—even though they are long dead—we operate within a set of rules that are largely outdated. These outdated rules cause problems: we react to crises late, we fail to capitalize on the front end of opportunities, and we don’t reach our potential.

We all laugh at the story of Blockbuster refusing to buy Netflix for $50 million in 2000, but few (read: none) of us knew what was possible with streaming. Plenty of smart people mistake “what I think is possible” for “what is possible”—especially in large corporations where change is perceived as risky.

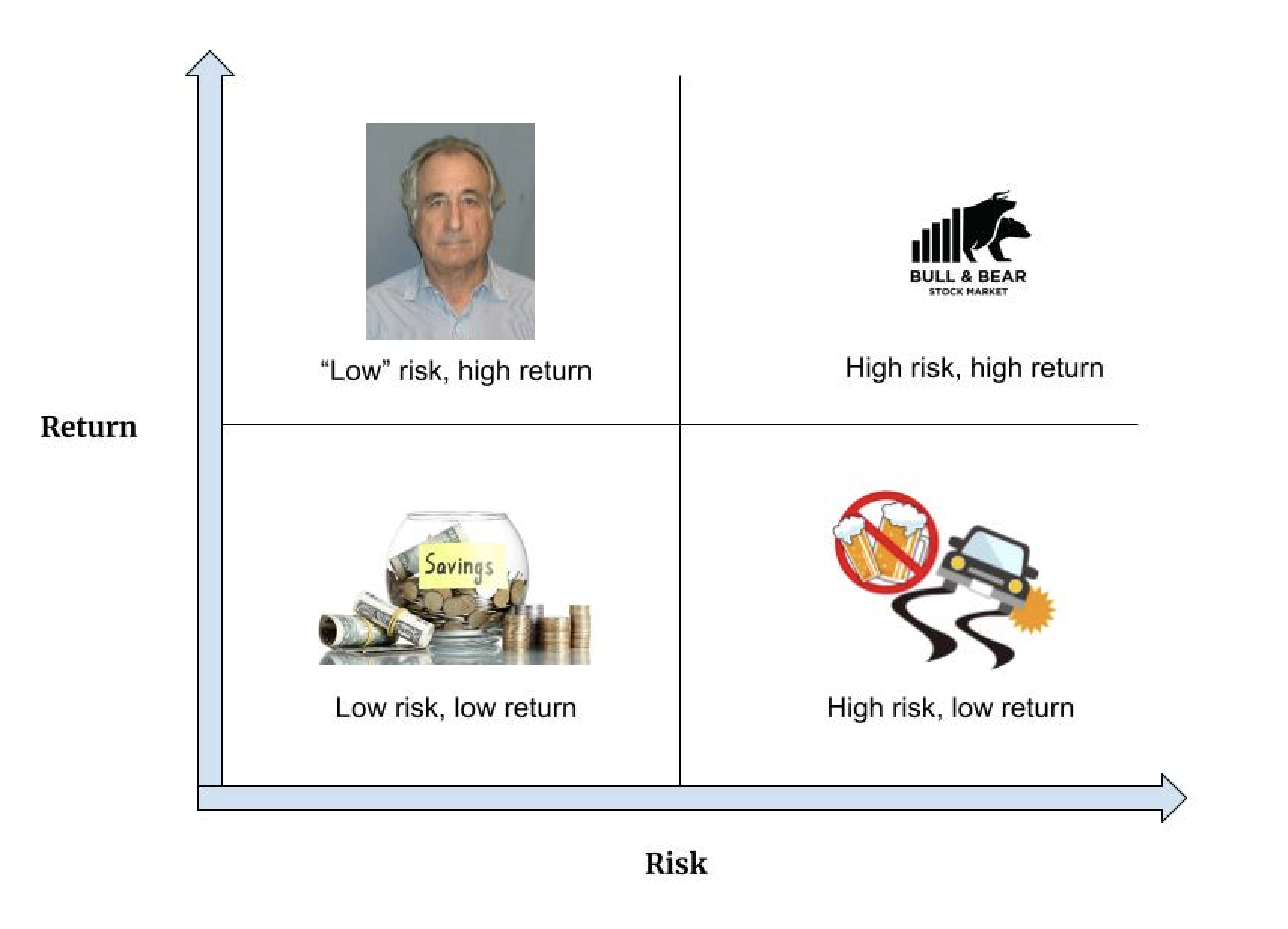

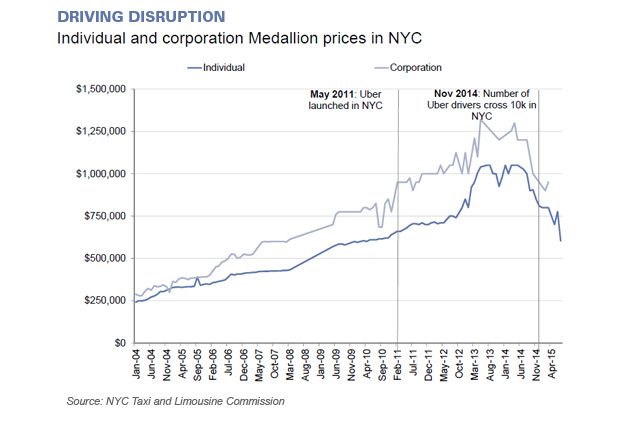

This “what is actually possible” mix-up happens with individuals too: the average price for an NYC taxi medallion was still more than $1 million in 2014, three years after ride-sharing emerged in the City. For comparison, the average price to buy an Uber medallion was, and still is, $0.00.

(Image source)

It’s impossible to know the future, so the secret of “visionaries” and “geniuses” is not foresight, but rather insight into what is currently possible. (Tim Urban explains this wonderfully in his lengthy Elon Musk post.)

It’s our duty to ourselves and to society to update our software regularly by questioning assumptions—even those that were true last year. This is only achieved by thinking independently, since popular opinion and the general consensus lag years (or decades) behind.

(I use this model when I think about the nature versus nurture debate. Yes, better computers—aka nature—can handle better software, but what matters most is that we are running the best and most updated software available—aka nurture. You can have the sleekest new PC for a brain, but if you are running Windows 1995 as your software, you will not reach your potential.)

SYSTEMS

The modern world is a complex web of systems; it is global in more than just the literal sense. Like most people, I tend to fixate on singular products/events at the expense of the big-picture systems. Part of this narrow focus is a lack of critical thinking, but I place equal blame on the instant analysis culture of Facebook, CNN, Twitter, etc.

The people with the most up-to-date mental software, on the other hand, tune out the instant analysis noise and focus on the underlying systems. Though no human can possibly understand all of the systems that run the world in 2020—that is beyond our hardware capabilities—seeing part of the bigger picture is still possible.

Ben Thompson, creator of the excellent Stratechery blog, wrote a brilliant post just five days after the June 2016 Brexit referendum. In it, Thompson addresses some of failures and looming crises that arise when we play by the rules of an outdated system.

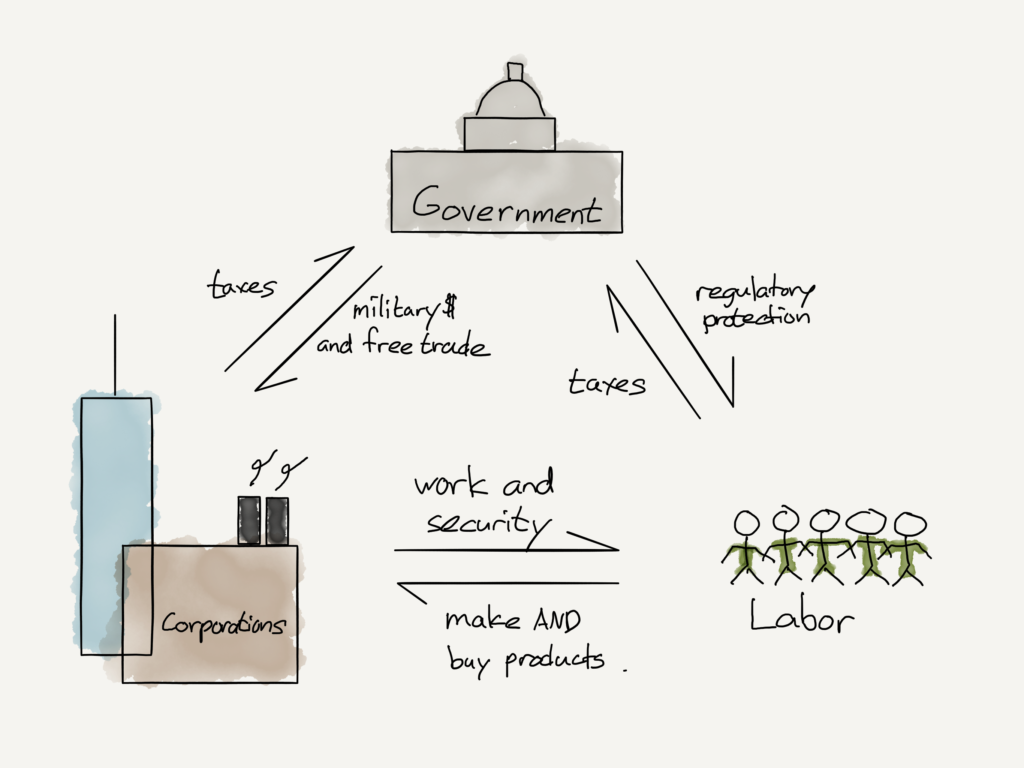

America’s institutions, from health insurance to pensions, are designed with the following system in mind.

(These diagrams are from Stratechery.)

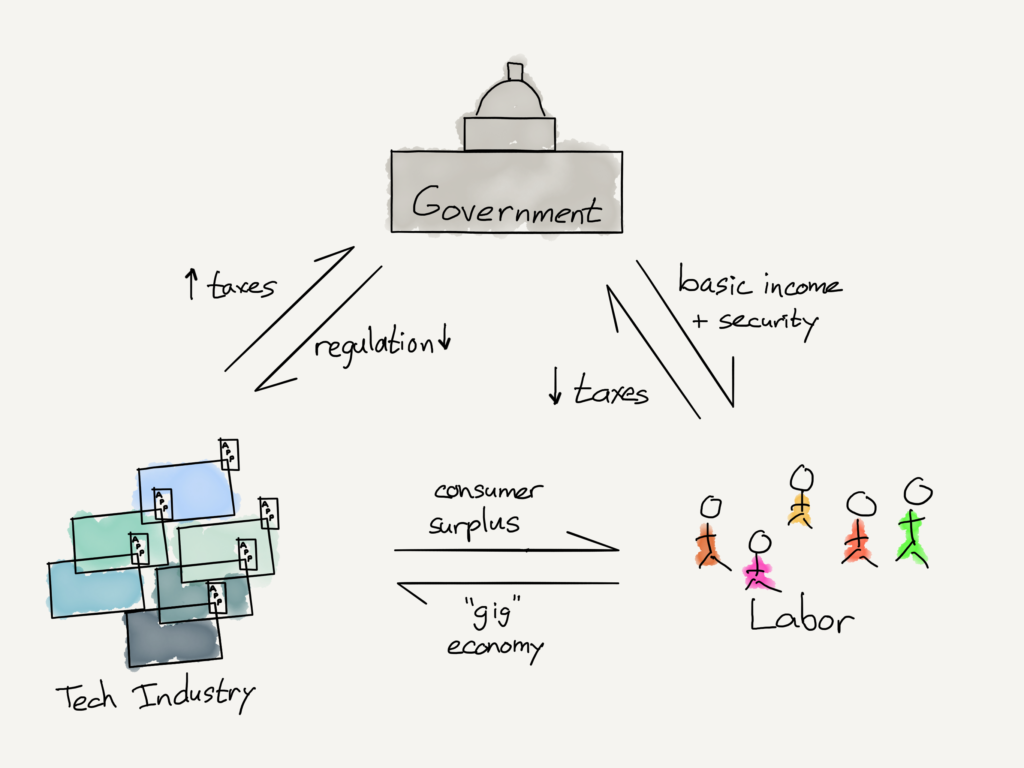

The problem is that every day we move farther away from that system and closer to the next system.

For the sake of brevity, I will oversimplify my summary of his post. If this topic at all interests you, I highly recommend reading it (link is in the above paragraph).

THE OLD SYSTEM: OVERSIMPLIFIED

Post-WWII, the United States extended its reach in the world. It promoted its system of government, large corporations, and labor. The U.S. spent extravagantly to create markets for its new giant industries; its goal was to provide aid in Europe and reduce trade barriers. These aid / barrier reductions would expand American industries, prevent another European War (we had just seen two horrible world wars), and constrain Communism.

Per Thompson:

“The implicit deal was this: the government created markets for the corporations, who in turn provided not just employment but also security for their employees, funding health insurance and pensions, while employees (and corporations) paid for the government: in 1960 the lowest income bracket paid 20%, while the highest paid 90%, and the corporate tax rate was 52%. Europe followed a similar model, but spared of the burden of a huge military, nationalized most social security programs, especially health care but also pensions.”

This was sustainable in a less globalized trading world, as was the case after the world wars. Starting in the 1970s, however, corporations began to flip the model on its head…

THE SHIFT / BACKLASH

Big corporations realized there was an easy way to increase profits: outsourcing production. Companies would still design the products here, but they’d outsource the production—aided in large part by China’s opening in 1978.

I mentioned this in a previous blog post, but this outsourcing of production was far from a crime against humanity. What we consider “low wages” by American standards lifted billions of people out of poverty, saving millions of lives in the process. As Thompson writes, trade is a “win-win.”

Though trade may be a net “win-win”, someone is always losing (e.g. the taxi drivers who bought medallions in 2015), so backlash is inevitable. In the case of globalization, millions of Americans have seen their jobs outsourced (and, increasingly, automated). People from all walks of life were affected, so uprisings emerged on the Left and Right: the Tea Party movement (2009) and Occupy Wall Street (2011) are probably the most notable. Though they exhibited different demands, both movements criticized the new model in which the elites profited off of globalization while the middle class was somewhat left behind.

Thompson helps us zoom out and see globalization, automation, the Tea Party, and OWS from a systemic view, giving us more perspective:

“It is foolish to think that a core component of society—labor—can be fundamentally changed without there being knock-on effects on the other components of that system … There are clear differences between the left and right: the former sees Wall Street or The City as the villain, while the latter blames immigration. [Yet] both want a return to the old deal: honest work for an honest wage.”

THE NEW REALITY

Simply put, we no longer live in a world where large corporations provide us security, pensions, and health insurance. A return to the old deal is not reasonable, and a return should not be our goal.

Why should we not return?

“While the first twenty years of the modern tech industry (starting with the personal computer) primarily benefited corporations, the last fifteen years have dramatically improved the quality of life for consumers. The defining quality of technology, particular Internet-based companies, has been the generation of massive amounts of consumer surplus.”

The “consumer surplus” emerged with the internet, and even more so in the smartphone era. How can you quantify the value of having all of your loved ones plus humanity’s entire knowledge in your pocket? The consumers are winning here.

Instead of seeking a return to the old world, we should embrace the information age and use its infinite possibilities to our advantage. How can we do this?

Google, Facebook, Amazon, etc. are all world-wide companies. As Thompson says, “there is no need for government support to open markets and guarantee trade […] Rather, it is the government that ought take a much more active role in supporting individuals.”

In other words, rather than supporting corporations (who in turn supported individuals), the government needs to cut out the middlemen and support individuals directly. This could involve a number of different policy initiatives:

Healthcare – Thompson: “For lots of reasons both practical and political, [universal health care] may not be viable in the U.S. Given that, Obamacare is a huge step in the right direction.” Wherever you fall politically, it is increasingly insane for us all to rely on employee-sponsored healthcare. Not only is it insane, it’s self-sabotaging—healthcare is a huge burden on the self-employed that prevents many would-be entrepreneurs.

The government should “loosen regulations and taxation around business creation” and “loosen regulations on the gig economy.” I won’t pretend to be an expert on this, but it does seem as if some states (like California) are actually doing damage with their means of addressing it. Rather than requiring Uber to provide healthcare for its “employees,” why not just separate healthcare and employment?

Thompson also mentions a potential UBI (*cough* Freedom Dividend *cough*) but I won’t waste words on this until Andrew Yang (and his ban on robocalls!! #Yang2020) gains more traction in this election.

The holdup?

If the general public is slow to move from “what we think is possible” to “what is possible,” the government is slower by a factor of 1,000.

WHAT MIGHT HAPPEN

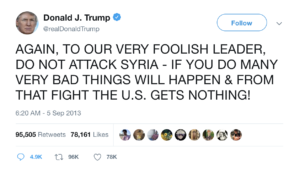

In the out-of-context words of Donald Trump, if we do not address these systemic changes, MANY VERY BAD THINGS MIGHT HAPPEN.

(note: this joke is not a political endorsement)

Thompson: “Globalization may have been the first shoe to fall on the middle class, but automation is the other, and it will affect just as many jobs as manufacturing, including—especially—white collar ones.”

An emphasis (like Trump’s) on bringing jobs back to America is shortsighted; widespread automation, not outsourcing, will be the labor shift that hits us the hardest. When thinking about automation, we tend to focus only on manufacturing jobs. This is because other industries haven’t been affected to the same degree as manufacturing has yet, so we assume that the status quo will always remain. This is a mistake. We should instead be observing the changes that are taking place and projecting them into a future that doesn’t yet exist (an example is asking what effect self-driving cars will have on America’s 3.5 million truck drivers; “no effect” is not the right answer).

Automation will be a net win. It will create amazing jobs that don’t exist today, and it will free us to do more meaningful work. Despite this, the shift may be very unpleasant if we don’t think ahead and prepare our society and its social safety-net. If we can ditch the short-term policy mindset and ask ourselves “what is really possible?”, we can prepare America for the world of 2040. The rules of 1970 will not cut it, for we’re playing in a different system.

To transition well, the new safety net has to be implemented correctly. Thompson: “higher tax rates to fuel a misguided attempt to recreate the 1950s would be just as much of a disaster as undoing the old deal has been for the middle class. The world has changed.”

Tech companies are the most powerful institutions in the U.S. now, and it’s in their own best interest to lead the way.

Thomson: "VCs in particular should be willing to close the carried interest loophole, and everyone in the industry should be willing to shoulder higher tax rates. The payoff is equilibrium: the chance to build fabulously successful businesses that go with the current, not against it. The alternative is far worse: once automation arrives, guess who is going to be the scapegoat?"

There will be no need for a scapegoat if we start updating our collective mental software.