The Scanning Age: Automation and America

The old rules are crumbling and nobody knows what the new rules are, so make up your own rules — Neil Gaiman

Of all the times to be alive since the first homo sapiens emerged, this is one of them. And it is a strange one. Most humans who have ever lived a) are dead and b) did not live through globally-historic events like the Black Plague or the World Wars. We are an exception, living through the birth of the digital age. Take a moment to think about this. Your ancestors who toiled anonymously on farms in Prussia were real people, just like you. And one of their children had a child who is your great-great-grandmother. This person never lived to see a photograph, much less a live stream of anything their mind could think of, all of the time.

It’s impossible to know exactly how special this moment will look in retrospect. Will people in 3021 remember the 21st century as the inflection point of our species? Will the pace of change keep accelerating until history becomes irrelevant and humans turn into cyborgs by 2121? Will we destroy ourselves before we can even answer these questions?

Regardless of the how this all ends, a lot is happening right now. A single revolution — such as the Civil Rights movement — is usually enough to change the fabric of society, but we have a boatload of revolutions happening at the same time: our mediums of communication, populist political movements, gender/identity rights, a new space race, and more. There are so many revolutions happening at the same time that it’s impossible to keep up with them all, much less make sense of them all.

Think of any movement or seismic change happening today, and ask yourself what it has in common with all of the ones listed above.

I’ll wait. [that long pause on Jeopardy! when a person gets stumped by a Daily Double and sees their life flash before their eyes]

It’s the internet. The internet is the real revolution, the forcing function behind all of the others, but it’s also put us in a weird limbo…

An analogy

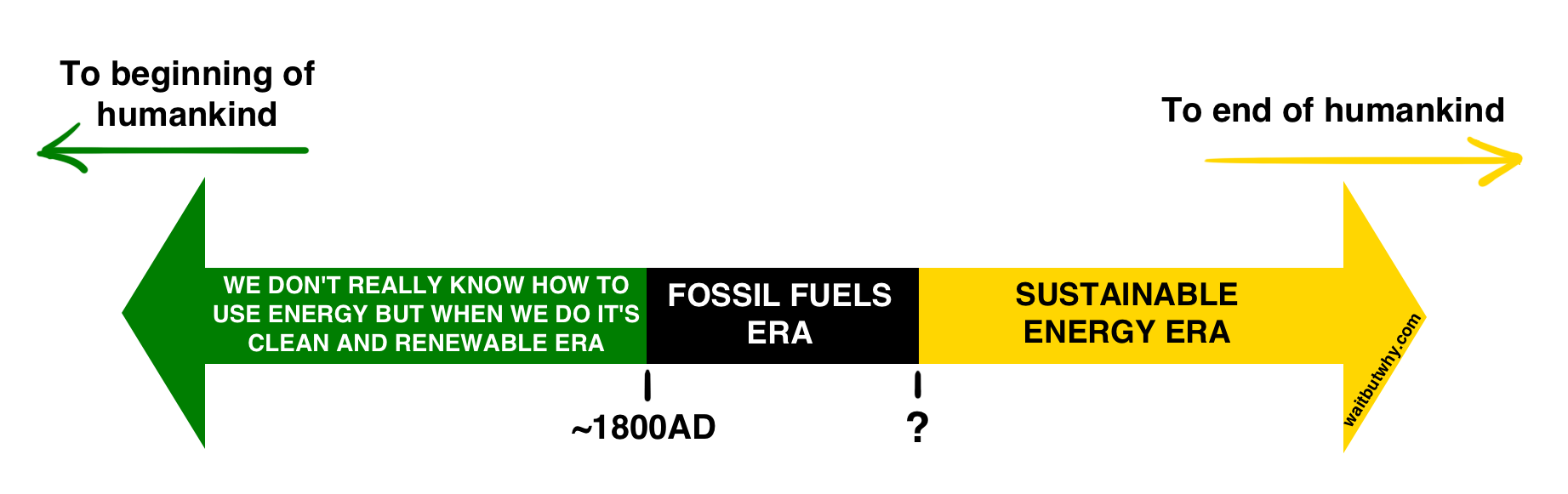

A few years ago, I was reading Tim Urban’s fantastic blog post about Tesla, and came across this graphic.

The fossil fuels era will be a blip on the radar of human existence, especially if we colonize Bezos’s space habitats and become interplanetary before the next nuclear war. Yet for many generations, including those reading this, the fossil fuels era is inseparable from the way that we view the world. When you zoom out, fossil fuels are a transition phase, but we live zoomed-in lives.

Just as we’re living through the black part of the timeline above, we’re also in the liminal state between the physical, analog world and the digital world. Albert Wenger, author of World After Capital, a great (and free) e-book, argues that this transition is actually the third great revolution for humankind.

Hunter-Gatherers → Agrarian Age → Industrial Age → (help it’s all happening at once) → Digital age

These historical categories may seem arbitrary, by Wenger’s thesis is that a new era beings when that which is most scarce changes. The four scarce resources have included food, land, capital, and human attention.

Scarcity for hunter-gatherers = food → scarcity for agrarians world = land → scarcity for industrial age = capital →(we are here)→ scarcity in digital age = human attention (I prefer to think of this as “the amount we can consume now far outweighs the amount of collective hours we have.” Or, ~260 million hours of YouTube content was added in 2019.)

We’re not all the way into the digital age, of course, as only the richest and financially free do not have to exchange their time for money (see part II).

Returning to the energy analogy

Sustainable, inefficient energy → fossil fuels → sustainable, powerful energy

Industrial/analog era → SCANNING PHASE → digital-native era

We’re in an awkward, puberty-like phase between the analog and digital era, like what I imagine happened when cars first emerged and killed half the horses on the road. One could call this time of transition a “scanning” phase, a term I heard coined by former Coinbase CTO, Balaji Srinivasan. Just as a scanned document is the compromise between a physical document and a digital-native text file, we are currently living in a world of physical institutions that have been scanned online.

An example of this is in banking.

Analog banking: physical banks that accept your cash deposits in those vacuum tubes and give you small business loans if they know you go to church, or something.

Scanned banking: The banking apps on your phone and the other big financial institutions that we have today. This is still a centralized system.

Digital-native banking: decentralized currencies like Bitcoin where there is no need for banks. As you are well aware, digital currencies already exist, but we’re still firmly in the scanning phase of banking.

Bitcoin in theory: as long as other people are willing to accept your digital coin as a medium of exchange, financial institutions and governments can no longer control or seize your wealth! This is great for people living under corrupt regimes.

Bitcoin in practice: oh sh*t there’s a finite number of Bitcoin, let’s treat it like a casino game so we can make real money like US dollars!**

**The USD has been decoupled from gold since 1971, so technically it’s also a figment of our imaginations. Fortunately, enough people believe in its strength that its not going to tank overnight (I’m no expert. It very well may tank tonight and be replaced by Dogecoin. This is not investment advice).

What are other, less messy examples of analog scans in our society?

Journalism

Analog journalism: Newspapers and their ilk

Scanned journalism: Ad-supported content / online publications / digital news outlets behind paywalls

Digital-native journalism: sovereign writers who are paid directly by their readers (See: the recent Substack revolution, or publications like Stratechery — Stratechery’s founder outlines the future of journalism in this 2020 post)

Education System

Analog journalism: the education system as we know it; advancement based on time-gating and age, as opposed to content mastery

Scanned journalism: I mean, nothing has really changed besides Zoom lectures and Khan Academy / online courses

Digital-native journalism: a digital-first education that promotes mastering a subject’s fundamentals instead of the usual sequence: a lesson, an A-F grade, and being shuffled along the assembly line even if you don’t know the fundamentals . One element of Balaji Srinivasan’s idea for affordable education is to provide blockchain nano-degrees instead of one “all-or-nothing” college degree. In other words, if you master the equivalent of 99% of a college physics degree, you have 99% of the physics degree credential and are highly employable. In today’s world, 99% of a degree is basically the same as 0% of a degree, and good luck finding a job!

________________________________________

PART II (published 08.15)

A one sentence recap of part one: We are living through one of the biggest transitions in human history as we leave the analog world and enter the digital; since we’re still in the midst of this shift, we see “scans” of the analog world all around us — like online banking and ad-supported journalism — that exist until digital-native products take over.

In part two, I want to zoom out and reflect on the job landscape as we move from the analog to the digital world:

*Automation is different this time *The scanning age is the speed bump that’s saving us *The end of the scanning age will be a good thing *The near term will become more painful if we keep our heads in the sand

Automation

To put it succinctly, many American jobs are being automated or have already been automated.

Machines execute repetitive tasks more cheaply, efficiently, and with fewer mistakes than people do. In the 20th century, we saw the rise of machines play out in cities like Detroit, where the longstanding middle class of assembly-line workers were largely automated, disappearing for good. The U.S. Rust Belt “employed 43 percent of aggregate employment in 1950, and just 27 percent in 2000” (source).

Nowadays, computers have simply expanded the horizon of what is considered a “repetitive task”. It now can include anything with specific instructions and defined parameters, like a website’s shopping cart or a game of chess.

We’re at the tip of the iceberg, as machine learning in the coming digital age will make today’s artificial intelligence look like WWII computing machines appear to us — laughable. Further examples of the iceberg’s tip:

*On the Radiology front, AI is now capable of surpassing medical experts in breast cancer prediction *Self-driving cars are progressing, and they will eventually displace truckers, bus drivers, and Ubers (the drivers, not the company), freeing billions of hours of human attention and saving lives *Amazon Go (a fascinating read) portends to make the grocery store cashier obsolete *Things like GPT-3 and chat bots reducing the need for many customer support jobs

Notice which jobs are not on the verge of automation. In the scanning age (see part one), “blue collar” jobs like plumbing and HVAC mirror their analog equivalents, since these jobs require physical skills and undefined parameters — the opposite of digital-native. Robots still look ridiculous when walking, for example.

Where is public sentiment right now?

The political debate surrounding the effects of automation doesn’t fall neatly into the usual two-party, black-and-white bloodthirst. Instead, it appears that most opinions fall somewhere between two (less politicized, for now) extremes in opinion: doom and gloom vs. nothing is wrong.

The argument on the nothing is wrong side of the debate is built on the concept of creative destruction: when a job dies off, usually through technical progress, a shiny new job is created somewhere else to replace it. This new job is often a by-product of the new technology itself (e.g. when cars arrived, taxi drivers replaced coachmen, and new auto mechanics appeared as well). Switchboard operators and wispy-moustache teenagers at Blockbuster have vanished, but we now have millions of software developers and a shortage of employees to fill them. In the nothing-is-wrong camp, job loss via automation will play out as it always has. There is no need to panic.

On the doom and gloom side of the debate, it is far too late to prevent the effects that AI will have on society. These people probably say that the climate crisis is unsalvageable too, and they are people to avoid at parties. In their eyes, there will be unfathomable income and resource inequality before we know it. These people are present throughout history.

As a tech optimist and someone who gets too excited and becomes delusional, I generally lean towards the nothing is wrong camp. I’ve come to believe, however, that this time is different. Doom and gloom is not inevitable, but a failure to act proactively will indeed lead us to a bad place.

Change is accelerating

Unlike most previous periods of creative destruction, the current wave of automation is the result of a massive paradigm shift: the analog world is becoming the digital world. As noted in part one, it’s not just that a great technology has emerged, but rather a new era of humanity. This is a special time to be alive, which is why I chose to be born in the 1990s instead of the 1340s.

Hunter Gatherer age → Agrarian Age → Industrial Age → Digital age

Change itself is accelerating. The hunter-gatherer age lasted hundreds of thousands of years; the agrarian age, thousands; the industrial age, hundreds; and the digital age is younger than most Facebook users.

Automation is different this time because the digital age plays by different rules. My concern is not the amount of disruption — society is incredibly adaptable when given time — but rather the speed at which it can happen. Sweeping changes occur faster now thanks to software, the internet, and zero friction to the spread of ideas. Legacy regulations and protections can only prevent the inevitable for so long in the face of a digital tsunami.

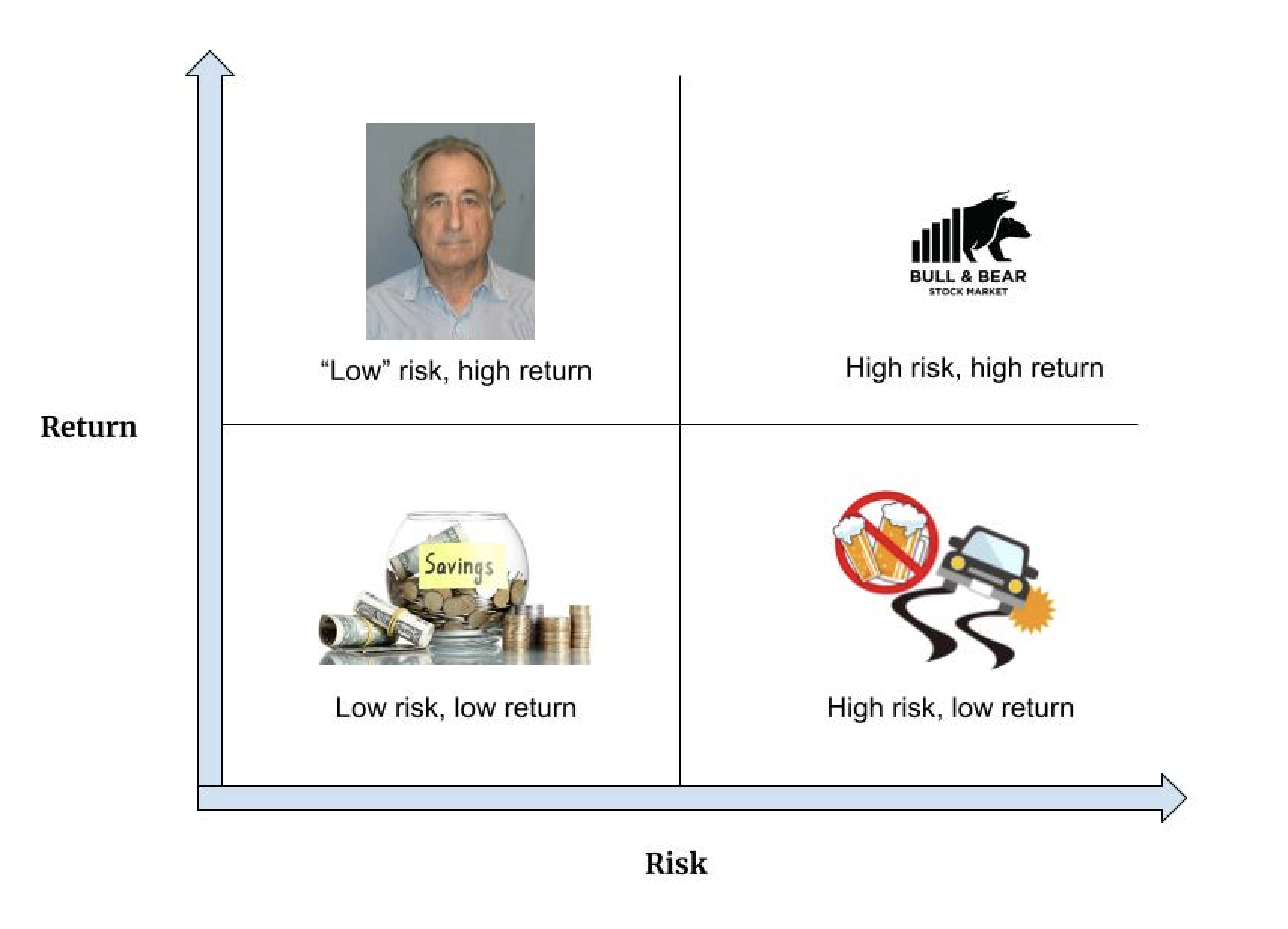

We as a nation/society aren’t acting proactively to prepare for the changes on the horizon. Part of the reason that we don’t plan ahead is that there is no historical precedent of labor changing this quickly. As Nassim Taleb wrote in his incredible book, Fooled by Randomness, when we imagine a “worst case” scenario, the historical “worst case” that has happened constrains our imagination. We forget, however, that at the time that this historical worst case happened, it exceeded the worst case that came before it.

If the past, by bringing surprises, did not resemble the past previous to it (what I call the past’s past), then why should our future resemble our current past?

Another reason we aren’t acting proactively is, of course, that nothing meaningful gets accomplished quickly in America, unless a pandemic or terrorist organization has already punched us in the face. The founding fathers designed checks and balances to prevent the president / ruling party from abusing power, and this distributed power keeps the pendulum from swinging too far, too quickly. There are times — like a pandemic or rapid automation — where the usual path of slowness comes back to bite us.

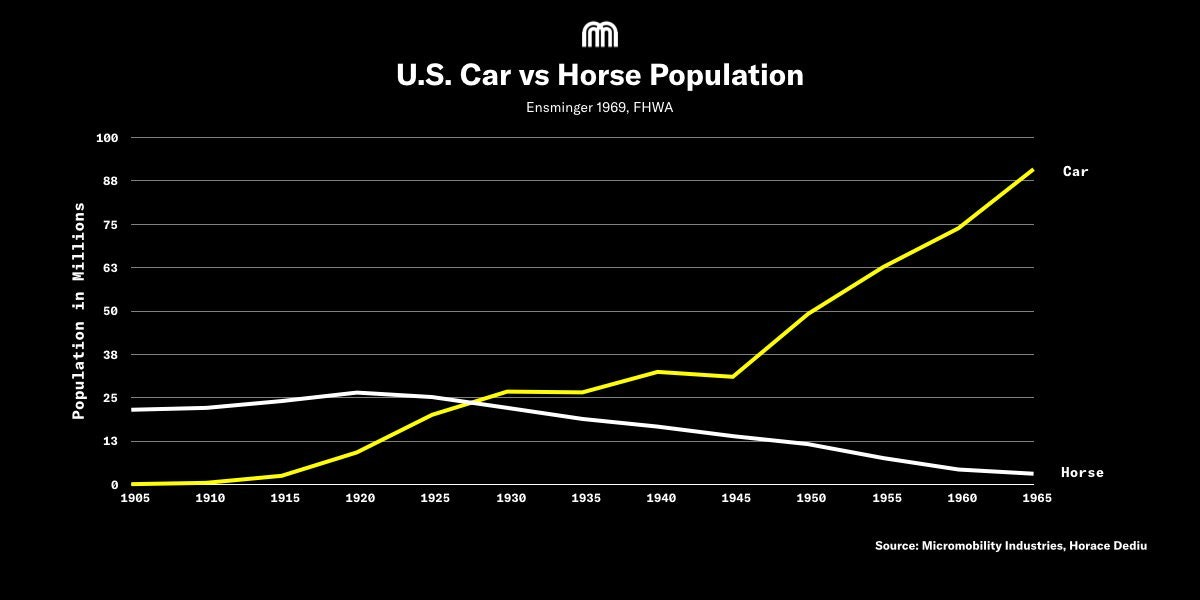

To be clear, there have been periods with more mind-blowing lifestyle changes than we are living through. An 80-year-old American born in 1875 lived through the birth of telephones, radios, airplanes, penicillin, nuclear weapons, both world wars, the discovery of general relativity, women’s suffrage, and the replacement of horses with cars. Automobiles took off during the 1910s, but it took 30+ years before the horse population was cut in half. Things evolved more slowly than they do now, but it’s worth noting that those 20 million horses never returned.

Flash forward to today. There are more than 3.5 million truck drivers in the USA, change is accelerating, and we seem to forget that as soon as cars can drive themselves, we become the horses. The acceleration of change brought by the new rules of the digital age is why there is no precedent in our lifetimes. Industries that we take for granted will vanish like the horse population, only more quickly. New jobs will emerge, but the interim won’t be peaceful.

Why we aren’t doomed yet: the scanning age

Since we have done very little to prepare for the coming disruptions, we’re lucky the full effects of automation have not arrived yet. If trucks are not driving themselves down the interstate, where does that leave us? Let’s return to the idea of the scanning age — the modern twilight zone.

Hunter Gatherers → Agrarian Age → Industrial Age → (scanning age) → Digital age

We previously discussed journalism, education, and banking in the scanning age, but what does the scanning age mean for labor as a whole? In a nutshell, modern “knowledge-work” jobs are the scans of their “white collar” analog/industrial equivalents. Jobs in insurance, sales, law, finance, HR, consulting, and dozens of other lines of work perform the same basic functions as they did in the analog world; they’ve simply been scanned online, where email chains, shared files, and Slack channels have replaced the drawers of paperwork, physical files, and landlines of yore. Even doctors now spend hours manually transferring their in-person observations and reports (read: their job) into online health platforms — a classic scanning age thing to do.

I do not believe that most of these knowledge-work jobs are a real advancement over their analog counterparts. Sure, we can share information more quickly now and stay in touch eternally, but the modern whirlwind/hive mind doesn’t always lead to actual improvements. For example, adding millions of reporting hours does not seem to make doctors anything but fatigued, and America’s health isn’t notably improving.

The silver lining, however, is that this scanning age of labor has bought us time before the looming automation brought by the digital-native world. As of 2021, we’ve seen an evolution in the labor landscape, not a revolution. But the revolution is coming.

The end of the scanning age is good

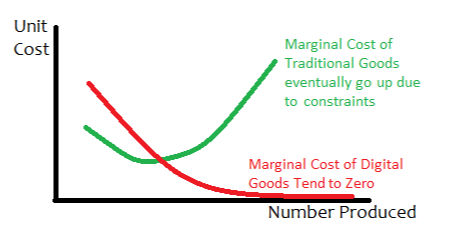

From a societal perspective, we are already seeing the awesome democratizing force of the internet. As mentioned in part one, power is shifting from the few to the many in finance, education, and publishing. In finance, big banks are already feeling the effects of cryptocurrency, lay-person day traders who can band together, and buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) platforms that aren’t designed to prey on consumers. In the media sphere, previously disenfranchised voices can now share their perspective virally thanks to the phenomenon of online content distribution’s zero marginal costs.

Zero marginal cost is the foundation of Albert Wenger’s World After Capital, from which I borrowed the concept of the four distinct human eras. Zero marginal cost is the principle that distributing content on the internet to each additional person (say, person 1,000) costs essentially zero compared to the cost of distributing content to person number 999.

The internet completely erased marginal costs, which is why we live in a new human era. In the previous age of marginal costs of distribution, The New York Times’s power was cemented by its massive distribution channels. When the cost of distribution vanished, the power of network effects took its place — i.e., “everyone is already on Facebook so the next person will join too.” This combination of zero marginal costs and network effects is what allowed Facebook and Google to become trillion-dollar companies.

Anyway, more people with influence, platforms, and the ability to stand up to centralized bullies means we’re becoming more democratic. Progress!

A digital-native world is better for human labor too

The internet has not fundamentally transformed office jobs (yet). Instead, most knowledge work is now a “stare at the computer” copy of its analog equivalent. Knowledge workers, living in an endless inbox of pseudo-productivity, behave a lot like their analog predecessors, and they appear no more physically, mentally, or spiritually healthy as a result. We do not exist to execute narrow, repeatable, mindless tasks like machines do. Instead, we evolved to solve problems and actually use our minds and bodies to improve ourselves, other people, and the world.

To be clear, the spectrum of “knowledge work” is vast, full of many fulfilling jobs (I like my own job!). But the end of the scanning age will be welcome.

Counterarguments

In his well-written argument, Eric Levitz says that automation is not as all-encompassing as people like Andrew Yang believe it to bee. Levitz is correct when he says new jobs emerge to replace the old (i.e. creative destruction), but he doesn’t acknowledge what can happen if the “destruction” part happens quickly and the “creative” part hasn’t caught up yet.

Another strain of counterargument that I’ve often heard seems to disapprove of technological progress altogether. “Where will workers find meaning in their lives if we automate their jobs?” they condescendingly ask.

The beauty of automating knowledge work is not that it will allow people to retire and sit around getting fat all day. That sounds amazing terrible. The beauty of this future automation is that it will free people to solve more meaningful challenges: climate change, aging infrastructure, absolute poverty, malnutrition/obesity, democratizing education, curing Alzheimer’s, etc. We won’t run out of things to do.

For millennia, we’ve slowly climbed the rungs of human progress. In the agrarian age, we relied on our own farming to survive. Before that, we relied on our own hunting to survive — are we worse off because we no longer die en masse during droughts? The next rung on the ladder of human progress is to upend this outdated belief that “feeding our children and living under a roof” requires an hourly job. We need not fear technological progress.

Returning to Ben Thompson’s Amazon Go article that I linked above.

“Marx saw a world where capital subjugated labor for its own return; technologies like Amazon Go have increasingly no need for labor at all. Some, certainly, see this as a problem: what about all the cashiers? What about all the truck drivers? What about all of the other jobs that will be displaced by automation? Well, I would ask, what about the labor of Marx’s day, the factory workers borne of the industrial revolution that he thought should overthrow the bourgeoisie? In fact, they are all gone, replaced by automation. And, in the meantime, nearly all of humanity has been lifted out of abject poverty […] The world is not static: to replace humans is, in the long run, to free humans to create entirely new needs and means to satisfy those needs. It’s what we do, and the faith to believe it will happen again will be the best guide in figuring out how.”

This is probably going to get uglier in the short run

If we learned anything from COVID, it’s that America is (thankfully, except in pandemic times) not a country where top-down dictates work very well, especially compared to China. Since that’s the case, we might as well embrace the inevitable and foster a graceful transition to the digital world, instead of looking backwards and making things harder on ourselves. Donald Trump promising Rust Belt workers that he’ll bring their jobs back from overseas grossly misses the point: these jobs are not coming back. New jobs will arise, but the old jobs no longer exist.

Both America-first protectionists and modern progressives who argue for 20th-century social-democratic tax laws are ignoring an important fact: economic freedom (i.e. not depending on the next paycheck to meet one’s basic needs) is not a zero-sum game.

As Naval Ravikant says, if we all had computer science or engineering degrees, we’d automate almost all of our jobs in 5 years and move on to more interesting work. This positive-sum game is why the pie keeps growing: Cornelius Vanderbilt did not have a computer or air conditioning, yet nobody thought he was poor.

Unfortunately, both the protectionist and “blame the wealthy” narratives have more political appeal than innovation does, and they have us on a path to some type of civil war/undoing. If you thought these recent populist movements were frightening, wait until millions of “white-collar” jobs are automated.

Getting in our own way

Many of our analog laws need to be reconsidered from scratch, though there is no evidence this is going to happen either. Governing the digital world with an analog-world lens is like using a 250-year-old document to decide whether AR-15s need regulation (can you imagine!). We seek to regulate Google as if it’s Standard Oil, yet we forget that Google, unlike old monopolies, does not need to restrict competition to dominate online search. Bing is just a click away, but few users are offended enough to ditch Google.

Until our aging politicians figure out how to reign in the software giants without trying them for antitrust violations that aren’t applicable to the digital age, we remain beholden to the wishes of a handful of CEOs.

More short term pain: Health insurance is still widely tied to traditional employment. This allocation process seems massively shortsighted, and it’s a barrier to the would-be entrepreneurs that are capable of solving our biggest challenges.

Conclusion: Optimism

Humans are adaptable, and I’m optimistic that the future (and the earth) will be a cooler place than it is today. But we must act proactively to make that future arrive sooner and less painfully.

Our goal should not be to return to the 1950s, but to make life 10x better come the 2050s. That might mean *eventually* adding something as drastic as a universal basic income to provide economic freedom that separates food/shelter from labor (though there could be serious UBE drawbacks), or instituting some type of VAT. I won’t pretend to be highly educated on these issues, so let’s just start with congressional term limits and call it a day.

Regardless, we need politicians who recognize that this is a different era of humanity, and we need to revisit our pre-digital laws and norms.