What I Learned Losing Money

NBA star Giannis Antetokounmpo was a poor, 18-year-old rookie from debt-ridden Greece when he was drafted by the Milwaukee Bucks and became a millionaire overnight. He went straight to the bank and discovered that only $250,000 could be fully protected, so he spread his money across numerous banks. The Bucks' owner personally intervened to teach Giannis about investing, but this anecdote is more than a cute story. Giannis was behaving rationally based on what he learned in his childhood: unexpected losses can occur when you invest.

That lesson is especially true when you are chasing higher returns.

In 2021, I heard an interview with Zac Prince, CEO of BlockFi, a cryptocurrency (e.g. Bitcoin) exchange platform. Flash forward to November 2022: BlockFi filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and froze the assets of all retail customers, myself included. I was literally sweating (from incredibly spicy fried rice, to be clear) as a I read the BlockFi news that all accounts were frozen. The following postmortem is meant to be educational, not a sob story (I did not invest enough to be ruined, OKAY?).

I divided this longer post into four sections:

A brief explanation of crypto exchanges and why Bitcoin was created in the first place (fear not, it's not a technical discussion because I'm not technical)

A few diagrams to explain the high-yield "savings" investment that I made

Things Fall Apart: implosion of the system, baby

The biggest lesson, which I believe is valuable to all investors

Background: Bitcoin and BlockFi

In the dark ages (say, 1994) before online transactions became viable, you could use cash, check, or credit cards without the government and big banks (which we'll call "central institutions") knowing where you are, what you're buying, and everything you've bought in the past year. Though privacy was pleasant, the limitation was that you had to physically drive to the Toys "R" Us at the mall to Christmas shop—much to Jeff Bezos' chagrin.

In our digital economy, you can buy nearly anything in the world without leaving your bed. The tradeoff is that your every purchase is recorded by the pesky central institutions. Less privacy, more convenience.

The first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, emerged in 2009 so that people could have the best of both worlds: digital transactions while avoiding the intrusion of central institutions via peer-to-peer payments. Central institutions are necessary in the digital economy because they inject trust into transactions. With Bitcoin, cryptography eliminates the need for trust, and therefore, eliminates the need for a credit card and verified identity in your purchase.

As it turns out, there are major challenges to Bitcoin's adoption as a currency:

Bitcoin's value fluctuates, as in, "the Bitcoin you used to buy a fake ID in 2014 is now worth $40,000."

For years, the acquisition/use of Bitcoin required digital savviness that few possess (e.g. having a crypto wallet). Using central institutions is more convenient.

Most governments oppose Bitcoin (as a currency) because it undermines power structures.

As Bitcoin became more popular, startups saw a financial opportunity to solve problem number two, the challenge of using and getting Bitcoin, so cryptocurrency exchanges like Coinbase and BlockFi emerged. These exchanges make money by providing you liquidity—always being there as a buyer and seller of crypto so that you don't have to transact with sketchy people online—and taking a cut of those transactions (exchanges do much more than provide liquidity, which we'll get to). This business is called market making; other examples of market makers are trading sites such as E-Trade or Robinhood.

The Irony of Central Exchanges

Recall that crypto's breakthrough was digital and decentralized money: both convenience and independence. The irony of these centralized crypto exchanges is that they remove all independence/decentralization—you literally upload both sides of your driver's license, your social security number, and a bank account to use an exchange. If you want to then use your new crypto to do something illegal (a major criticism of crypto is that it facilitates sex trafficking and other heinous crimes), you're no longer anonymous.

If crypto exchanges are digital but centralized, which is the complete opposite of why crypto was created, why do they exist at all? They exist because crypto diverged from its original purpose of privately buying things online. Crypto instead became a speculative asset—something to bet on to get rich quickly. Thus, the lack of privacy doesn't matter if the goal is to sell Bitcoin or other crypto for a profit of US dollars.

How the BlockFi "Savings" Account Worked

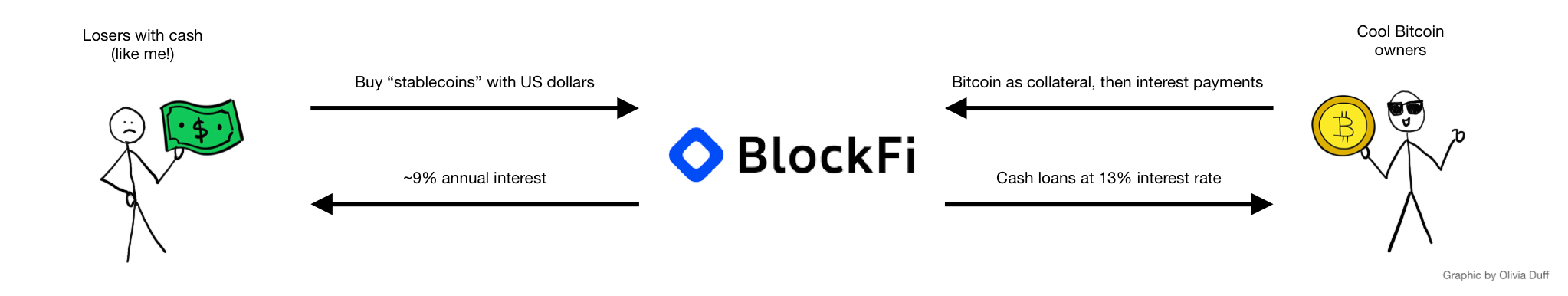

In reality, crypto exchanges do much more than sit between buyers and sellers of Bitcoin. BlockFi, for instance, offered a high-interest "savings" account: any retail customer could earn 9% interest on their first $20,000 that they deposit with BlockFi "stablecoins" (crypto tokens that are backed 1:1 by US dollars). With most bank's savings rates at 0.25%, I took BlockFi up on that offer and deposited some cash.

Wait a second!! How could BlockFi offer an interest rate 36x higher than other savings rates?

Believe it or not, some people out there (read: crypto bros) had most of their net worth tied up in Bitcoin, especially during the COVID Bitcoin spike. Even though some of these crypto bros had lots of paper wealth, many of them were "Bitcoin poor" and needed US dollars. (Being Bitcoin poor is like being "house poor," in that both groups of people have a cash shortage. The house-poor person has a house instead of cash, though, while the Bitcoin-poor person has some digital tokens and limited sexual contact instead of cash.)

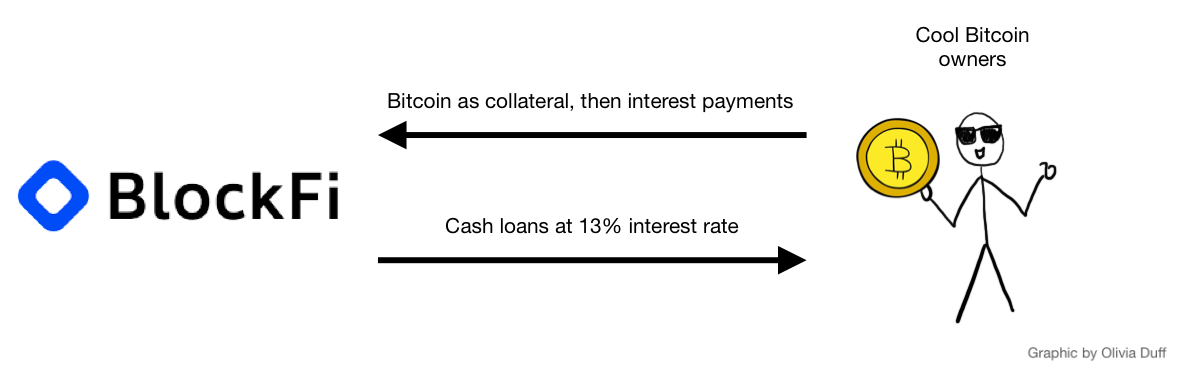

So, the Bitcoin poor needed cash and didn't want to sell their Bitcoin, so BlockFi seized the opportunity. Crypto bros could deposit their Bitcoin (as collateral) and borrow cash from BlockFi. Interest rates on that borrowing varied, but we'll use 13% for this example.

Where do I come in? I, and other retail investors, deposit cash with BlockFi, giving BlockFi the US dollars to lend at 13% to crypto bros. Thus, BlockFi can offer retail investors like me a 9% savings rate and still pocket 4%, plus fees.

As I wrote above in Bitcoin challenge number three, the US Government does not permit this type of crypto lending in "real" banks, so an unregulated player like BlockFi saw a potential windfall—a windfall that made sense for all 3 sides on paper.

You idiot, Paxton! What if the price of Bitcoin goes down enough so that the crypto bros can't repay their loans to BlockFi, even with collateral? Where would BlockFi find the cash to give back to you?

Believe it or not, I asked these questions.

BlockFi had a huge stockpile of its own assets (reportedly $3 billion of its $9 billion), including "SEC-regulated equities" (read: stocks), that it kept with third parties. In the event Bitcoin plummeted and people stopped repaying loans, BlockFi was legally required to burn through its growing stockpile of assets before a retail customer's deposit could possibly be impacted.

But your deposit is not protected! Only official banks offer FDIC insurance for retail investors, which protects your first $250,000 in the event a bank collapses. How would BlockFi find any cash to return your initial deposit, much less your interest?

That's fair, but if the price of Bitcoin started to collapse, I'd most likely have time to withdraw my money given BlockFi's large margin. What could possibly go wrong?

Things Fall Apart

Last year, this guy's face became all-too-familiar.

In November 2022, Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF), CEO of FTX, went from poster boy of crypto to an indicted money launderer and fraudster. To make a long story extremely short:

SBF founded two separate companies: a crypto hedge fund called Alameda research (in 2017) and a cryptocurrency exchange called FTX (in 2019).

As Alameda's trading losses mounted, FTX secretly lent them several billion dollars from FTX customer deposits, a super-illegal action called “commingling funds." (SBF also took a billion dollar loan from Alameda to fund his lifestyle and his red-flag-in-hindsight huge political donations.)

As part of the clandestine FTX loan to Alameda, Alameda pledged FTX’s own crypto token, FTT, as collateral. That’s right, FTX gave Alameda real customer money and Alameda put up FTX's own made-up security as collateral. If Alameda lost the money, its collateral, FTT, would have nothing backing it, making it worthless. And Alameda kept losing money.

The CEO of a rival crypto exchange, Binance, caught wind of Alameda’s insane balance sheet and announced Binance was selling all of its FTT, realizing that its $500 million collection of magic beans (FTT) might turn into a bunch of worthless digital tokens very quickly. After Binance's announcement, investors panicked and tried to withdraw $8 billion from FTX, so FTX froze withdrawals because it obviously did not have $8 billion available. Again, Alameda lost that money.

When FTX failed during its "bank" run, it was exposed as a massive fraud. Everyday customers lost faith in other crypto exchanges en masse and rushed to withdraw their own crypto deposits. More runs!

Bank Runs

Banking in the game Monopoly is not like banking in real life. In real life, banks only keep a proportion of customer deposits in liquid assets, and they can lend the rest to borrowers, or buy bonds, etc. This practice is called "fractional-reserve banking."

If a bank only has 5% of customer deposits readily available as cash, what happens if a few large customers withdraw all of their money and others start to worry since the bank has limited cash on hand? Wouldn't the bank fail—as portrayed in It's a Wonderful Life—if all the other customers panicked and asked for their money too?

Bank runs were indeed a risk until the Great Depression, when the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created to insure depositors (now up to $250,000) if their bank fails. Incidentally, as we learned with the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the federal government is willing to insure far more than $250,000 for the sake of maintaining stability.

Trust is what actually keeps the modern banking system afloat.

That trust does not exist in the world of crypto, though, where the US government does not provide salvation. If FTX runs out of liquidity (i.e. they can't return your money), they have to find immediate credit help from a partner or they die. Needless to say, nobody was in a rush to provide credit to fraudster SBF.

Anyway, BlockFi

In mid-2022, one of BlockFi's largest borrowers, a hedge fund called Three Arrows Capital, collapsed. BlockFi lost about $80 million and was rescued by FTX (oh no) through a credit line of about $250 million. At the time, this rescue wasn't extremely concerning for depositors of BlockFi. FTX was a hugely successful institution, and BlockFi gave FTX the right to acquire it, meaning BlockFi customers would be "fine" if BlockFi had another cash crunch.

Although BlockFi wasn't commingling any funds, they (like everyone) only held 5% of customer deposits actively and reportedly stored the other 95% with another exchange called Gemini—founded by the Winklevoss twins, of all people.

In November, FTX collapsed, and a week later Gemini paused customer withdrawals amidst a liquidity crunch. In summary: BlockFi's holder of deposits (Gemini) paused withdrawals and their biggest lender committed historic fraud and failed.

Unsurprisingly, BlockFi did not have a bunch of money sitting around when its retail customers went to withdraw money, so they froze the platform.

"Bank" runs everywhere. No FDIC insurance anywhere. SBF is a fraud and everything he touches dies.

The Lesson: There are no Free Lunches

You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool - Richard Feynman

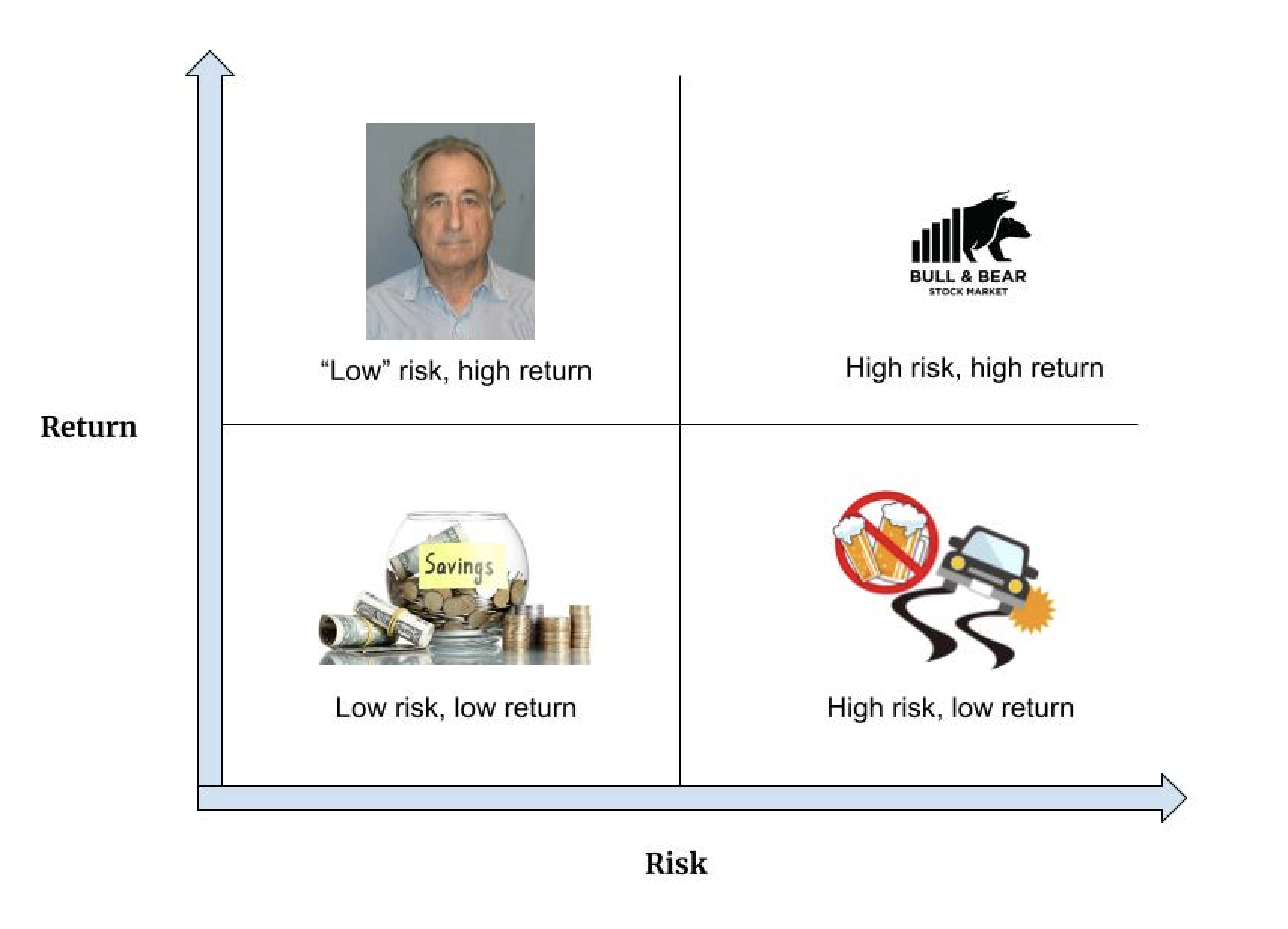

Every investment falls somewhere on this risk-return matrix.

The problem is that the low-risk/high-return "free lunches" don't exist. They can appear to exist for a very long time, however, because risk is not always obvious. Three examples:

For years, your investment fund provides you an oddly-consistent killing on paper until you suddenly lose both your profits and your principal when you find out that Madoff Investment Securities LLC is a Ponzi scheme.

You buy a second home knowing that you can sell it for a $50,000 profit in 8 months like your cousin did—easy money. Sadly, it's 2008 and you end up way underwater.

You understand that BlockFi has reserves and collateral and isn't doing sketchy stuff, but you ignore counterparty risk and the potential failure of all of crypto exchanges.

Even if you are a professional arbitrageur or a Russian tech wizard who is front-running stock trades, you have to either accept risk or be content with lower returns. The free lunch will taste great now and give you crippling food poisoning later.

Risk is Part of Life — Use the Barbell

I was inspired to write this post while reading Nassim Taleb's book, Antifragile. Taleb writes about the nature of manmade systems like the global economy: because billions of irrational humans are involved, the economy is complex in ways that we cannot begin to understand. As a result, we have no idea when the wildly unexpected will happen or what the unexpected will be. Taleb calls these unforeseen events—like 9/11, or the collapse of the housing market because of subprime loans—"Black Swans."

Just as we can't predict Black Swans because of the world's complexity, we can't quantify precisely how risky an investment is. Our salvation, however, is that we can generally say whether something is risky or not risky (e.g. an index of tech stocks that bear risk versus $1,000 in a savings account).

Since we're able to make that binary distinction between risky and not risky, we're able to deploy a method called "barbell investing." As Morgan Housel writes in The Psychology of Money:

I think of my own money as barbelled. I take risks with one portion and am terrified with the other... I just want to ensure I can remain standing long enough for my risks to pay off. You have to survive to succeed.

As someone with (hopefully) many decades of investing in front of me, I have no desire to avoid risk. Sometimes, I'll lose money as a result of that choice, but the idea is that the risk will pay off in the long run. What I cannot accept is donning rose-colored glasses and getting sucked into the allure of free lunches. The barbell is a more sustainable way to survive. The Bucks' owner can learn something from Giannis too.